Ellen McLaughlin's Helen, Directed by Shannon Davis I:

Playwright Ellen McLaughlin

Ellen McLaughlin and the Theatre Communications Group have kindly granted us permission to reprint Ms. McLaughlin's opening essay on her play Helen, a very free variation on Euripides' tragicomedy, Helen, which is currently in production at the University Theatre, University of Wisconsin-Madison, under the direction of Shannon Davis.

Introduction

Euripides’ Helen is surely one of the strangest plays ever written. I have Brian Kulick to thank for turning my attention to it. Brian has always had an uncanny ability to steer me toward the most challenging and provocative texts. He was the person who suggested that I adapt Electra for a production The Actors’ Gang in L.A. was putting together of The Oresteia. This production would instigate my trilogy, Iphigenia and Other Daughters, as well as Chuck Mee’s Orestes and Agamemnon 2.0. Not bad for one dramaturgical idea. But then Brian has one of the great ears—he genuinely seems to listen to the particular playwright’s voice, and that receptiveness to nuance and idiosyncrasy makes him capable of suggesting what a writer seems to want to grapple with, even when the writer herself does not know. I must also thank Liz Engelman, a dramaturg of unparalleled faith and determination, who, because she simply wouldn’t give up on me, basically made me write the play. I’d been asked to be part of the Women Playwrights Festival at ACT in Seattle, where Liz was then working—a festival that was shaped around the readings of four playwrights’ newest work, followed by a retreat at Hedgebrook artists colony on Whidbey Island. This was all very well in theory, but I couldn’t seem to write a play.

I’d been through the crucible of the opening of my play Tongue of a Bird at The Public Theater to resoundingly dreadful reviews all around and I had consequently not been able to write so much as a postcard for nearly a year. When, in the winter of 1998, Liz asked me to consider doing this thing in May 1999, I’d thought, well, by then I’ll either be writing again or I’ll have to kill myself, so why not? But by April, though I still had a pulse, I was apparently incapable of even considering getting back in the shark-infested water that was the playwright’s existence, as I saw it. After weeks of staring into the remorseless blankness of my computer screen and my own mind, gibbering with frustration, I called Liz. For weeks, she’d been gently prodding me with emails about the need to see the play so they could cast it and so forth. Her cheerful tone had become somewhat strained as the days and weeks went by and I kept stalling, thinking I could write something or other before anyone had to know what a total washout I was. I finally had to admit that not only did I not have a play to send her, I didn’t have an idea for a play. The only thing I could think to do at that late date was to back out and hope they could find some playwright who could take my place. There was a pause and then Liz said, “If you wrote one page, we would produce it. We’ll wait. See what you can do.” So while I was wiping tears of amazement and gratitude from my face.

I recalled that Brian Kulick, who was the associate director at The Public when Tongue of a Bird was produced there, had said at the time that he thought I should take a look at Euripides’ Helen, wherein Helen never goes to Troy at all, having been replaced by a simulacrum, made by the gods, who is taken to Troy in her place while the real Helen spends the entire war in Egypt, evading the wandering hands of the pharaoh’s son and waiting for Menelaus to come pick her up after the war is over. Most peculiar. Euripides wrote it, as far as we can make out, in 412 B.C., which was precisely the point at which the first reports were just coming back to Athens concerning the calamitous outcome of their expedition against Sicily. The city was in shock, beginning to take in just how disastrous that imperial venture had been. (Not a single boat came back. Of the Athenians who weren’t killed outright, a vast number ended up working and dying as slaves in the quarries of Syracuse.) Rather than write something along the lines of The Trojan Women, an outright cri de coeur against war and its horrors, of which the Athenians were all too aware at the moment, he wrote Helen, which is unlike anything else we have in the canon of classic plays.

Helen is what might be called a tragicomedy and the sense of it is somewhat surreal, at least to modern ears. The basic premise seems absurd and slightly amusing at the same time that there is something terrifically disturbing about the whole thing. As one might suspect, the play involves a number of recognition scenes—the Greek equivalent of double and triple takes—as Helen has to say, over and over again, that yes, it really is she and she’s been here, in Egypt, of all places, all this time.

Menelaus comes off as something of a buffoon and the ending devolves into hijinks as he and Helen try to figure out how they are going to escape and hie themselves back to Sparta without being stopped by the feckless new pharaoh, who, unlike his dead father, is something of a cad and has designs on Helen that don’t need to be enumerated. But there are a few needle points of perplexity and despair that Euripides conceals in the froth of that demi-farce. Early on in the play, Helen is confronted by a Greek soldier who, after finally being convinced that she is who she seems to be, lets out a howl of disbelief and horror at the thought that so many should have died for a mere phantom, for nothing, in fact. Helen herself is nonplussed by this, but then she would be. Later, when Menelaus has been led to the same improbable truth and she asks him to take her home, now that it’s all over, he hesitates, just for a line or two, but it is enough to discomfit. If she wasn’t there, in Troy, then she’s not really the one who matters, not the one they fought the war over, he thinks, and taking her home won’t make any sense of the whole senseless business of the war they all went through. But Euripides has the simulacrum vanish miraculously in a puff of smoke shortly after this conversation, and consequently Menelaus has no actual choice to make. He can either take the real Helen home or take home nothing.

Euripides’ Helen is far smarter than his Menelaus and handily persuades him past his slight wobble in resolve. Still, that moment interested me. And I’m sure it didn’t pass unnoticed by the audience at the first production either. To find that a ghastly war was fought under false pretenses makes the war almost unthinkably obscene—a truth Americans are all too familiar with at this moment in our history. Consequently, this play becomes one of the greatest, if strangest, antiwar plays ever written, and it continues to disturb centuries later.

I take greater liberties with this text than I have taken with any of the others, but I still feel that fundamentally, it is a fairly direct response to what the Euripides text invokes. This is a play that takes beauty quite seriously, as I think the Greeks did. The power of the phenomenon of human beauty still awes and mesmerizes us many centuries later, and we are still in the grip of a kind of psychotic addiction to it, certainly in this culture. There are Helens aplenty in the modern world, and I suppose always will be.

My Helen is self-aware, conscious of the eerie powerless power she embodies, and no less in the thrall of it than any of her admirers are, since she’s been one of its chief victims. She is an odd conflation of every modern notion of beauty bound to celebrity, from Jackie through Marilyn to Diana, as much as she is the quintessential Helen of myth. She is what Helen has become, what she has morphed into over time, but she is still what birthed the ideal. It is, not surprisingly, an overwhelming identity to maintain, as it has been for every Helen throughout human history. I was first intrigued by the play because I’d always had such trouble summoning compassion for the mythical figure. Who can take her seriously? Not even Helen herself can manage to, it seems. But as I got a chance to work with the figure I found herquite compelling and complex. It is her very ambivalence about her power that interests. She certainly benefits from it—she gets through the bloodbath of the war fought in her name without so much as breaking a fingernail apparently, whether she spends the time in Troy or not. According to legend, unfazed by the mayhem she has unleashed, she then lives to simper charmingly with Menelaus in Sparta over the absurdity of it all when Telemachus visits the couple years later in The Odyssey. She was worshipped as a goddess in her home city, Sparta, and most myths imply that she sidled into the pantheon after her death and was rendered eternal in the bargain. No one, not even the Trojans she destroyed, could help worshipping her, but though she inspires awe, she never seems to inspire much affection. How could she, since everywhere she goes she wreaks havoc? Still, she seems to do virtually nothing other than look like herself.

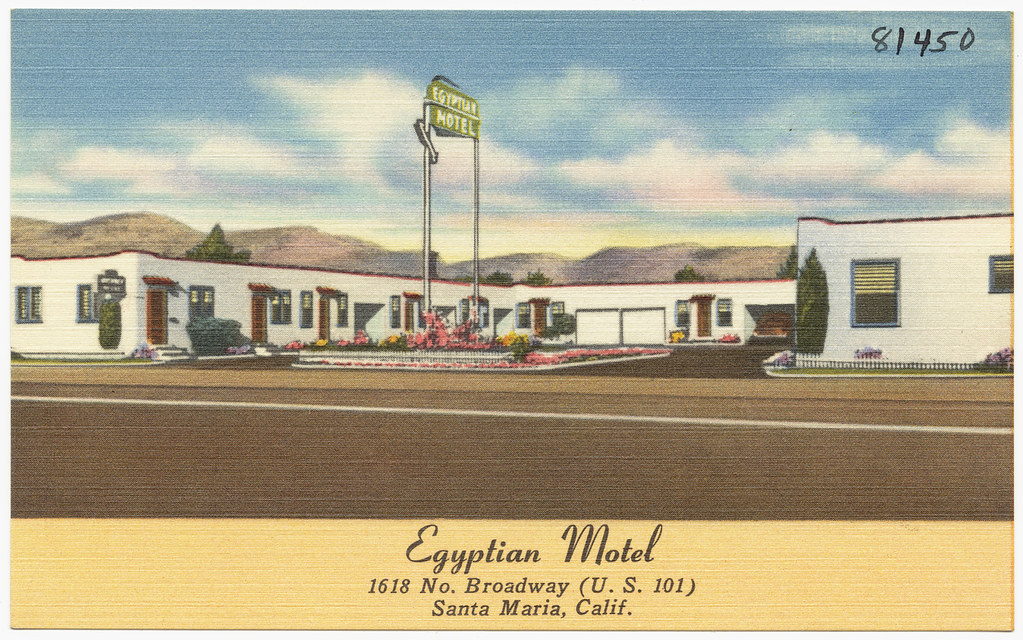

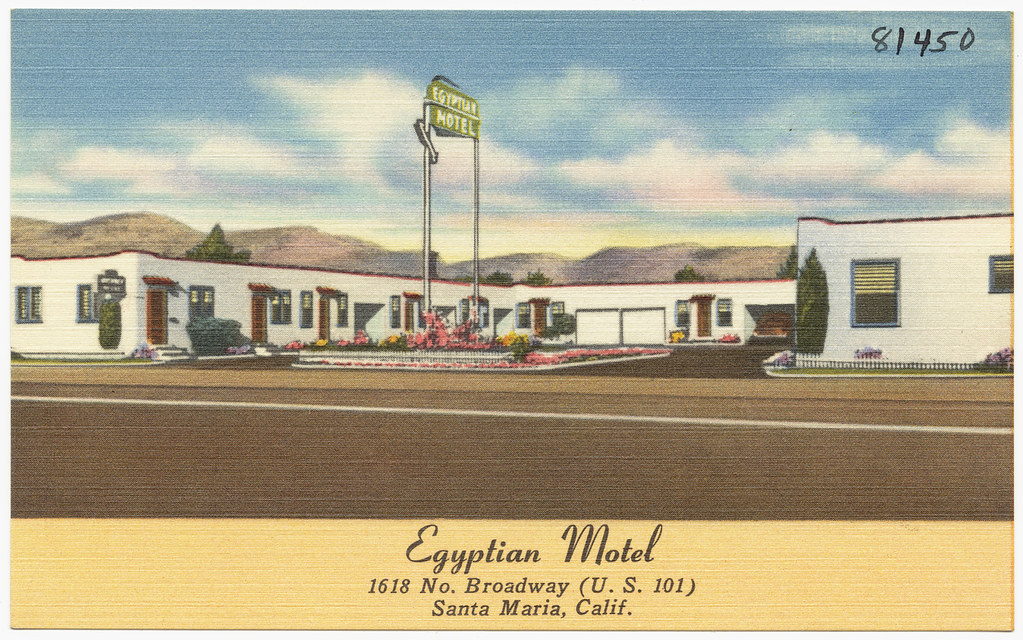

David's The Love of Helen and Paris.

Even the conventional story of the inception of the war seems to rob her of agency for her fate. She is always said to have been abducted by Paris, who ranks as the callow villain of the piece. She never has much say in the matter, either as to whether she wishes to go to Troy or whether she wishes to go home again once the damage is done. She goes, or is taken, where legend demands. Since she is never so much as nicked by the course of events and arrives wherever myth transports her looking as enchanting and flawless as she was when she started out, it’s hard to see her as having any real character to speak of, which is to say dimension, a quality only mutability and agency can lend. I came to think that there was something poignant about a character of such awesome stature who has no legitimate claim to the authentic, tragic weight of most epic figures. This has something to do with the preternatural quality of beauty itself, which has nothing to do with character, justice or, indeed, truth. Beauty is simply endowed to her, as it is to all such entities, fictional or not, and it is their peculiar blessing and curse for as long as it lasts. Much of the play has to do with Helen’s contemplation of this phenomenon—beauty—that she embodies. It is a contemplation she has been undertaking for all the years of her strange entrapment, and her partner in metaphysical discussion is, for the most part, the Servant.

The Servant is the most powerful figure in the play and the most elusive character for an actor to grasp. I was blessed in The Public Theater production to have the mighty and unique Marian Seldes interpret the role. She taught me a great deal about this character’s sly subversiveness, her hidden grandeur, and her dry humor. The Servant has been Helen’s sole intimate and confidant for seventeen years. She’s also been the sole victim of her pettish rages and fits. Yet most importantly, she has been Helen’s storyteller.

Helen is addicted to narrative (having been deprived of her own) and the two of them have a ritual that has been enacted daily over the years, wherein the Servant tells Helen stories. But not just any stories—the Servant has been telling Helen stories that are all versions of her own myth—there are, after all, an infinite number. Why does she do this? For all these years, the Servant has been tracking her charge’s progress toward enlightenment and prodding her

along, using various techniques. But there is a sense that today is the day; today Helen must be

brought to a recognition of her real story, her own story, of which she will have to acknowledge herself the author, and she must be brought to the understanding that the end of it is something she will have to write alone. Still, before she can do that, she will have to learn several things. Some she will learn from her visitors and some from the Servant herself, who will take their usual discussions to the next necessary step each time, nudging Helen toward consciousness of her capabilities and her ability to choose her fate rather than remain in passivity. But as much as the Servant is highly aware of everything that happens in the room, and is wise, even compassionate at times, these two people are heartily sick of each other as well, and their perpetual familiarity has bred a fair amount of weary bickering. The Servant is, as much as anything, preparing her mistress for the time when they will finally be free of each other. Nevertheless, there should be tenderness at times, particularly in the final section, when the Servant at long last tells Helen her own story. This is an act of compassion and high imaginative verve and it should leave Helen poised on the very brink of the most important decision she will ever make. I decided to bring Io in at the beginning of the play, though it makes no sense, as Helen points out, in terms of the chronology of myth. Io is one of the most ancient examples of the mortal girl raped by Zeus. And she pays a terrible price for his singling her out: she is transformed into a cow and persecuted for years by Hera’s gadfly. But I liked the notion of these two icons of exceptional female fate conversing with each other. They are bookends of a sort, the forerunner and the apotheosis of a kind of female singularity. And Io’s narrative of exile and transmutation is important for Helen to hear, as is her forthright relationship to her own destiny. I also liked the idea of beginning the play with a character who is so genuinely benign, guileless and funny as a foil for Helen’s tarter edge. She is also more worldly than Helen, having seen far more of the world than she ever wanted to, and her suffering has ennobled her rather than crushed her spirit.

Helen, for all of her sophistication, is not particularly worldly, having been protected from all that by her special status, and it is appropriately startling and sobering for her to encounter this particular figure. The pairing of these two characters also gives me the opportunity to have two mortal women, colleagues, as it were, speak to each other about the odd trials and perils of being female. I wrote the part of Io for Johanna Day, who played it with the kindof depth and sharp pathos that only a really great comic actor can bring to such a part.

I chose Athena to be the herald of the news of what happened at Troy because, again, I thought this would be a fun conversation to overhear. I wanted the most male-identified female divinity (the goddess of war, after all) to encounter this ideal of the female, because the friction would be greatest and the conflict most fruitful. Helen is, to be sure, terrified, at least initially, by this goddess, much more than she would be by anyone else from the pantheon, male or female, and yet she needs to be able to hold her own with her, possessing as she does a mastery Athena never obtained. Though Athena is indisputably the more powerful of the two, Helen’s self-possession and beauty rankle a bit and unsettle her. They should match each other, in other words, one paragon meeting another. As has been the case in all my writings about the Trojan War, the First World War, in all its lengthy absurdity and horror, is what Athena describes when she speaks of the Trojan War. This, more than anything, is what disorients Helen in the encounter. The poetry that’s been skidding through her head all these years is impossible to assimilate into this nightmare of waste and futility.

Menelaus is not a buffoon, however befuddled he may be by the radically disorienting phenomenon he encounters as soon as he comes to consciousness. Indeed, he is a decent man who has been trying for years to make sense of his impossible predicament. I don’t think there is any question about whether he loves his wife, and the choice he must make at the end is wrenching, given his feeling for her. But he is trying to do the right thing by all the victims of an apparently senseless war and he makes his choice accordingly. I don’t think these characters ever touch in the scene; they are, in a strange way, past that. What we see at the very end of the scene is an old married couple, speaking as intimately and as tenderly as people ever speak. This makes his exit all the more devastating for them both.

Helen’s day-to-day existence is strange indeed and it might be helpful to elaborate on it briefly. Though she is trapped in this tarted-up holding pen of a hotel room, she is not in anything like limbo. She does actually age and she can feel the time weighing on her. She doesn’t in fact eat or sleep, as she says, but there is still the division of the years into days and nights, each one of which she manages to get through by use of a series of rituals. In this sense she bears a resemblance to Winnie in Beckett’s Happy Days, whom I’ve always found strangely heroic in her ability to organize her time into a succession of meaningless rituals. Helen is rightfully proud of her fly swatting, a skill she has honed with her years of practice, and that gives her some tiny, if dwindling, satisfaction over the course of the day while it occupies the time. Since she dismantles her elaborate hairdo every night, she and the Servant must reconstruct it every morning, a fairly arduous task, at least for the Servant, who must also entertain her with a story. But this must be somewhat satisfying for both of them, the finished product being, of course, once again, absolutely perfect. Together, they are the custodians of this extraordinary thing—the Helen—and I don’t think it ever ceases to amaze them once they create it. And then there is the poetry, all fragments from The Iliad, which Helen isn’t in control of; it just occurs to her occasionally, out of the blue, and I don’t think she has any idea where it comes from.

I’ve always been interested in the old notion that it was Helen herself who wrote The Odyssey and that she commissioned or compelled Homer to write The Iliad. The sense was that The Odyssey was so grounded in a female sensibility that no man could have written it. Odysseus is taught, painfully and over the course of the long years of his travel, everything he needs to know to reenter human society after the dehumanizing trauma of war. And each of his mentors, divine or mortal, is female. I liked the idea that Helen was, unwittingly or not, the author of the Trojan War, and that she might actually be the author of the story as well.

So I had an aspect of her long process of self-discovery be the claiming of that story. This is partly my own notion of this odd business of being a writer. We are, most of us, ostensibly marginal to history, witnesses at the best of times, but often not even that. Our claim to our stories has less to do with our participation in narratives than it does with a deep preoccupation, an empathic dreaming into those truths. We earn the right to tell the stories because they matter to us. After a while, they live in us, getting into the bloodstream until the time they finally belong to us and teach us how to speak them. So my gift to Helen is to give her the opportunity, not to reenter the myth that outstripped her individual self so long ago, but to step outside of it and take her place in the margins, where writers stand. When it comes to true immortality, stories are all we mortals will ever know of the divine.

They’re what counts.

Ellen McLaughlin's Helen, Directed by Shannon Davis II:

The idea of Helen of Troy as the author of The Odyssey is one that haunts the ending of Ellen McLaughlin's free adaptation of Euripides' Helen (see McLaughlin's essay above), and it is one with a notable pedigree. Although he never assigns the great epic of ancient Greek literature directly to Helen, the famous nineteenth century British novelist, Samuel Butler (The Way of All Flesh, Erewhon), detected a distinct feminine voice in the epic's storied verse, much as Harold Bloom argues for the Jahwist in the Tanakh as being a royal woman of Solomon's court in his The Book of J.

In The Authoress of the Odyssey, Butler deftly reveals his evidence for reassigning what was thought to be Homer's to an unknown Sappho or Praxilla. Here is part of Butler's first chapter in his study, whose ideas inform the final scene of McLaughlin's play:

Samuel Butler, Self-Portrait

Playwright Ellen McLaughlin

Ellen McLaughlin and the Theatre Communications Group have kindly granted us permission to reprint Ms. McLaughlin's opening essay on her play Helen, a very free variation on Euripides' tragicomedy, Helen, which is currently in production at the University Theatre, University of Wisconsin-Madison, under the direction of Shannon Davis.

Introduction

Euripides’ Helen is surely one of the strangest plays ever written. I have Brian Kulick to thank for turning my attention to it. Brian has always had an uncanny ability to steer me toward the most challenging and provocative texts. He was the person who suggested that I adapt Electra for a production The Actors’ Gang in L.A. was putting together of The Oresteia. This production would instigate my trilogy, Iphigenia and Other Daughters, as well as Chuck Mee’s Orestes and Agamemnon 2.0. Not bad for one dramaturgical idea. But then Brian has one of the great ears—he genuinely seems to listen to the particular playwright’s voice, and that receptiveness to nuance and idiosyncrasy makes him capable of suggesting what a writer seems to want to grapple with, even when the writer herself does not know. I must also thank Liz Engelman, a dramaturg of unparalleled faith and determination, who, because she simply wouldn’t give up on me, basically made me write the play. I’d been asked to be part of the Women Playwrights Festival at ACT in Seattle, where Liz was then working—a festival that was shaped around the readings of four playwrights’ newest work, followed by a retreat at Hedgebrook artists colony on Whidbey Island. This was all very well in theory, but I couldn’t seem to write a play.

I’d been through the crucible of the opening of my play Tongue of a Bird at The Public Theater to resoundingly dreadful reviews all around and I had consequently not been able to write so much as a postcard for nearly a year. When, in the winter of 1998, Liz asked me to consider doing this thing in May 1999, I’d thought, well, by then I’ll either be writing again or I’ll have to kill myself, so why not? But by April, though I still had a pulse, I was apparently incapable of even considering getting back in the shark-infested water that was the playwright’s existence, as I saw it. After weeks of staring into the remorseless blankness of my computer screen and my own mind, gibbering with frustration, I called Liz. For weeks, she’d been gently prodding me with emails about the need to see the play so they could cast it and so forth. Her cheerful tone had become somewhat strained as the days and weeks went by and I kept stalling, thinking I could write something or other before anyone had to know what a total washout I was. I finally had to admit that not only did I not have a play to send her, I didn’t have an idea for a play. The only thing I could think to do at that late date was to back out and hope they could find some playwright who could take my place. There was a pause and then Liz said, “If you wrote one page, we would produce it. We’ll wait. See what you can do.” So while I was wiping tears of amazement and gratitude from my face.

I recalled that Brian Kulick, who was the associate director at The Public when Tongue of a Bird was produced there, had said at the time that he thought I should take a look at Euripides’ Helen, wherein Helen never goes to Troy at all, having been replaced by a simulacrum, made by the gods, who is taken to Troy in her place while the real Helen spends the entire war in Egypt, evading the wandering hands of the pharaoh’s son and waiting for Menelaus to come pick her up after the war is over. Most peculiar. Euripides wrote it, as far as we can make out, in 412 B.C., which was precisely the point at which the first reports were just coming back to Athens concerning the calamitous outcome of their expedition against Sicily. The city was in shock, beginning to take in just how disastrous that imperial venture had been. (Not a single boat came back. Of the Athenians who weren’t killed outright, a vast number ended up working and dying as slaves in the quarries of Syracuse.) Rather than write something along the lines of The Trojan Women, an outright cri de coeur against war and its horrors, of which the Athenians were all too aware at the moment, he wrote Helen, which is unlike anything else we have in the canon of classic plays.

Helen is what might be called a tragicomedy and the sense of it is somewhat surreal, at least to modern ears. The basic premise seems absurd and slightly amusing at the same time that there is something terrifically disturbing about the whole thing. As one might suspect, the play involves a number of recognition scenes—the Greek equivalent of double and triple takes—as Helen has to say, over and over again, that yes, it really is she and she’s been here, in Egypt, of all places, all this time.

Menelaus comes off as something of a buffoon and the ending devolves into hijinks as he and Helen try to figure out how they are going to escape and hie themselves back to Sparta without being stopped by the feckless new pharaoh, who, unlike his dead father, is something of a cad and has designs on Helen that don’t need to be enumerated. But there are a few needle points of perplexity and despair that Euripides conceals in the froth of that demi-farce. Early on in the play, Helen is confronted by a Greek soldier who, after finally being convinced that she is who she seems to be, lets out a howl of disbelief and horror at the thought that so many should have died for a mere phantom, for nothing, in fact. Helen herself is nonplussed by this, but then she would be. Later, when Menelaus has been led to the same improbable truth and she asks him to take her home, now that it’s all over, he hesitates, just for a line or two, but it is enough to discomfit. If she wasn’t there, in Troy, then she’s not really the one who matters, not the one they fought the war over, he thinks, and taking her home won’t make any sense of the whole senseless business of the war they all went through. But Euripides has the simulacrum vanish miraculously in a puff of smoke shortly after this conversation, and consequently Menelaus has no actual choice to make. He can either take the real Helen home or take home nothing.

Euripides’ Helen is far smarter than his Menelaus and handily persuades him past his slight wobble in resolve. Still, that moment interested me. And I’m sure it didn’t pass unnoticed by the audience at the first production either. To find that a ghastly war was fought under false pretenses makes the war almost unthinkably obscene—a truth Americans are all too familiar with at this moment in our history. Consequently, this play becomes one of the greatest, if strangest, antiwar plays ever written, and it continues to disturb centuries later.

I take greater liberties with this text than I have taken with any of the others, but I still feel that fundamentally, it is a fairly direct response to what the Euripides text invokes. This is a play that takes beauty quite seriously, as I think the Greeks did. The power of the phenomenon of human beauty still awes and mesmerizes us many centuries later, and we are still in the grip of a kind of psychotic addiction to it, certainly in this culture. There are Helens aplenty in the modern world, and I suppose always will be.

My Helen is self-aware, conscious of the eerie powerless power she embodies, and no less in the thrall of it than any of her admirers are, since she’s been one of its chief victims. She is an odd conflation of every modern notion of beauty bound to celebrity, from Jackie through Marilyn to Diana, as much as she is the quintessential Helen of myth. She is what Helen has become, what she has morphed into over time, but she is still what birthed the ideal. It is, not surprisingly, an overwhelming identity to maintain, as it has been for every Helen throughout human history. I was first intrigued by the play because I’d always had such trouble summoning compassion for the mythical figure. Who can take her seriously? Not even Helen herself can manage to, it seems. But as I got a chance to work with the figure I found herquite compelling and complex. It is her very ambivalence about her power that interests. She certainly benefits from it—she gets through the bloodbath of the war fought in her name without so much as breaking a fingernail apparently, whether she spends the time in Troy or not. According to legend, unfazed by the mayhem she has unleashed, she then lives to simper charmingly with Menelaus in Sparta over the absurdity of it all when Telemachus visits the couple years later in The Odyssey. She was worshipped as a goddess in her home city, Sparta, and most myths imply that she sidled into the pantheon after her death and was rendered eternal in the bargain. No one, not even the Trojans she destroyed, could help worshipping her, but though she inspires awe, she never seems to inspire much affection. How could she, since everywhere she goes she wreaks havoc? Still, she seems to do virtually nothing other than look like herself.

David's The Love of Helen and Paris.

Even the conventional story of the inception of the war seems to rob her of agency for her fate. She is always said to have been abducted by Paris, who ranks as the callow villain of the piece. She never has much say in the matter, either as to whether she wishes to go to Troy or whether she wishes to go home again once the damage is done. She goes, or is taken, where legend demands. Since she is never so much as nicked by the course of events and arrives wherever myth transports her looking as enchanting and flawless as she was when she started out, it’s hard to see her as having any real character to speak of, which is to say dimension, a quality only mutability and agency can lend. I came to think that there was something poignant about a character of such awesome stature who has no legitimate claim to the authentic, tragic weight of most epic figures. This has something to do with the preternatural quality of beauty itself, which has nothing to do with character, justice or, indeed, truth. Beauty is simply endowed to her, as it is to all such entities, fictional or not, and it is their peculiar blessing and curse for as long as it lasts. Much of the play has to do with Helen’s contemplation of this phenomenon—beauty—that she embodies. It is a contemplation she has been undertaking for all the years of her strange entrapment, and her partner in metaphysical discussion is, for the most part, the Servant.

The Servant is the most powerful figure in the play and the most elusive character for an actor to grasp. I was blessed in The Public Theater production to have the mighty and unique Marian Seldes interpret the role. She taught me a great deal about this character’s sly subversiveness, her hidden grandeur, and her dry humor. The Servant has been Helen’s sole intimate and confidant for seventeen years. She’s also been the sole victim of her pettish rages and fits. Yet most importantly, she has been Helen’s storyteller.

Helen is addicted to narrative (having been deprived of her own) and the two of them have a ritual that has been enacted daily over the years, wherein the Servant tells Helen stories. But not just any stories—the Servant has been telling Helen stories that are all versions of her own myth—there are, after all, an infinite number. Why does she do this? For all these years, the Servant has been tracking her charge’s progress toward enlightenment and prodding her

along, using various techniques. But there is a sense that today is the day; today Helen must be

brought to a recognition of her real story, her own story, of which she will have to acknowledge herself the author, and she must be brought to the understanding that the end of it is something she will have to write alone. Still, before she can do that, she will have to learn several things. Some she will learn from her visitors and some from the Servant herself, who will take their usual discussions to the next necessary step each time, nudging Helen toward consciousness of her capabilities and her ability to choose her fate rather than remain in passivity. But as much as the Servant is highly aware of everything that happens in the room, and is wise, even compassionate at times, these two people are heartily sick of each other as well, and their perpetual familiarity has bred a fair amount of weary bickering. The Servant is, as much as anything, preparing her mistress for the time when they will finally be free of each other. Nevertheless, there should be tenderness at times, particularly in the final section, when the Servant at long last tells Helen her own story. This is an act of compassion and high imaginative verve and it should leave Helen poised on the very brink of the most important decision she will ever make. I decided to bring Io in at the beginning of the play, though it makes no sense, as Helen points out, in terms of the chronology of myth. Io is one of the most ancient examples of the mortal girl raped by Zeus. And she pays a terrible price for his singling her out: she is transformed into a cow and persecuted for years by Hera’s gadfly. But I liked the notion of these two icons of exceptional female fate conversing with each other. They are bookends of a sort, the forerunner and the apotheosis of a kind of female singularity. And Io’s narrative of exile and transmutation is important for Helen to hear, as is her forthright relationship to her own destiny. I also liked the idea of beginning the play with a character who is so genuinely benign, guileless and funny as a foil for Helen’s tarter edge. She is also more worldly than Helen, having seen far more of the world than she ever wanted to, and her suffering has ennobled her rather than crushed her spirit.

Helen, for all of her sophistication, is not particularly worldly, having been protected from all that by her special status, and it is appropriately startling and sobering for her to encounter this particular figure. The pairing of these two characters also gives me the opportunity to have two mortal women, colleagues, as it were, speak to each other about the odd trials and perils of being female. I wrote the part of Io for Johanna Day, who played it with the kindof depth and sharp pathos that only a really great comic actor can bring to such a part.

I chose Athena to be the herald of the news of what happened at Troy because, again, I thought this would be a fun conversation to overhear. I wanted the most male-identified female divinity (the goddess of war, after all) to encounter this ideal of the female, because the friction would be greatest and the conflict most fruitful. Helen is, to be sure, terrified, at least initially, by this goddess, much more than she would be by anyone else from the pantheon, male or female, and yet she needs to be able to hold her own with her, possessing as she does a mastery Athena never obtained. Though Athena is indisputably the more powerful of the two, Helen’s self-possession and beauty rankle a bit and unsettle her. They should match each other, in other words, one paragon meeting another. As has been the case in all my writings about the Trojan War, the First World War, in all its lengthy absurdity and horror, is what Athena describes when she speaks of the Trojan War. This, more than anything, is what disorients Helen in the encounter. The poetry that’s been skidding through her head all these years is impossible to assimilate into this nightmare of waste and futility.

Menelaus is not a buffoon, however befuddled he may be by the radically disorienting phenomenon he encounters as soon as he comes to consciousness. Indeed, he is a decent man who has been trying for years to make sense of his impossible predicament. I don’t think there is any question about whether he loves his wife, and the choice he must make at the end is wrenching, given his feeling for her. But he is trying to do the right thing by all the victims of an apparently senseless war and he makes his choice accordingly. I don’t think these characters ever touch in the scene; they are, in a strange way, past that. What we see at the very end of the scene is an old married couple, speaking as intimately and as tenderly as people ever speak. This makes his exit all the more devastating for them both.

Helen’s day-to-day existence is strange indeed and it might be helpful to elaborate on it briefly. Though she is trapped in this tarted-up holding pen of a hotel room, she is not in anything like limbo. She does actually age and she can feel the time weighing on her. She doesn’t in fact eat or sleep, as she says, but there is still the division of the years into days and nights, each one of which she manages to get through by use of a series of rituals. In this sense she bears a resemblance to Winnie in Beckett’s Happy Days, whom I’ve always found strangely heroic in her ability to organize her time into a succession of meaningless rituals. Helen is rightfully proud of her fly swatting, a skill she has honed with her years of practice, and that gives her some tiny, if dwindling, satisfaction over the course of the day while it occupies the time. Since she dismantles her elaborate hairdo every night, she and the Servant must reconstruct it every morning, a fairly arduous task, at least for the Servant, who must also entertain her with a story. But this must be somewhat satisfying for both of them, the finished product being, of course, once again, absolutely perfect. Together, they are the custodians of this extraordinary thing—the Helen—and I don’t think it ever ceases to amaze them once they create it. And then there is the poetry, all fragments from The Iliad, which Helen isn’t in control of; it just occurs to her occasionally, out of the blue, and I don’t think she has any idea where it comes from.

I’ve always been interested in the old notion that it was Helen herself who wrote The Odyssey and that she commissioned or compelled Homer to write The Iliad. The sense was that The Odyssey was so grounded in a female sensibility that no man could have written it. Odysseus is taught, painfully and over the course of the long years of his travel, everything he needs to know to reenter human society after the dehumanizing trauma of war. And each of his mentors, divine or mortal, is female. I liked the idea that Helen was, unwittingly or not, the author of the Trojan War, and that she might actually be the author of the story as well.

So I had an aspect of her long process of self-discovery be the claiming of that story. This is partly my own notion of this odd business of being a writer. We are, most of us, ostensibly marginal to history, witnesses at the best of times, but often not even that. Our claim to our stories has less to do with our participation in narratives than it does with a deep preoccupation, an empathic dreaming into those truths. We earn the right to tell the stories because they matter to us. After a while, they live in us, getting into the bloodstream until the time they finally belong to us and teach us how to speak them. So my gift to Helen is to give her the opportunity, not to reenter the myth that outstripped her individual self so long ago, but to step outside of it and take her place in the margins, where writers stand. When it comes to true immortality, stories are all we mortals will ever know of the divine.

They’re what counts.

From Greek Plays by Ellen McLaughlin, published by Theatre Communications Group. Copyright © 2005 by Ellen McLaughlin. Used by permission of Theatre Communications Group.

Ellen McLaughlin's Helen, Directed by Shannon Davis II:

The idea of Helen of Troy as the author of The Odyssey is one that haunts the ending of Ellen McLaughlin's free adaptation of Euripides' Helen (see McLaughlin's essay above), and it is one with a notable pedigree. Although he never assigns the great epic of ancient Greek literature directly to Helen, the famous nineteenth century British novelist, Samuel Butler (The Way of All Flesh, Erewhon), detected a distinct feminine voice in the epic's storied verse, much as Harold Bloom argues for the Jahwist in the Tanakh as being a royal woman of Solomon's court in his The Book of J.

In The Authoress of the Odyssey, Butler deftly reveals his evidence for reassigning what was thought to be Homer's to an unknown Sappho or Praxilla. Here is part of Butler's first chapter in his study, whose ideas inform the final scene of McLaughlin's play:

Samuel Butler, Self-Portrait

"If, then, poetesses were as abundant as we know them to have been in the earliest known ages of Greek literature over a wide area of Greece, Asia Minor, and the islands of the Ægæan, there is no ground for refusing to admit the possibility that a Greek poetess lived in Sicily B.C. 1000, especially when we know from Thucydides that the particular part of Sicily where I suppose her to have lived was colonised from the North West corner of Asia Minor centuries before the close of the Homeric age. The civilisation depicted in the Odyssey is as advanced as any that is likely to have existed in Mitylene or Telos 600-500 B.C., while in both the Iliad and the Odyssey the status of women is represented as being much what it is at the present, and as incomparably higher than it was in the Athenian civilisation with which we are best acquainted. To imagine a great Greek poetess at Athens in the age of Pericles would be to violate probability, but I might almost say that in an age when women were as free as they are represented to us in the Odyssey it is a violation of probability to suppose that there were no poetesses.

The poets Sappho and Erinna by Simeon Solomon

We have no reason to think that men found the use of their tongue sooner than women did; why then should we suppose that women lagged behind men when the use of the pen had become familiar? If a woman could work pictures with her needle as Helen did, and as the wife of William the Conqueror did in a very similar civilisation, she could write stories with her pen if she had a mind to do so.The fact that the recognised heads of literature in the Homeric age were the nine Muses—for it is always these or 'The Muse' that is involved, and never Apollo or Minerva—throws back the suggestion of female authorship to a very remote period, when, to be an author at all, was to be a poet, for prose writing is a comparatively late development. Both Iliad and Odyssey begin with an invocation addressed to a woman, who, as the head of literature, must be supposed to have been an authoress, though none of her works have come down to us. In an age, moreover, when men were chiefly occupied either with fighting or hunting, the arts of peace, and among them all kinds of literary accomplishment, would be more naturally left to women. If the truth were known, we might very likely find that it was man rather than woman who has been the interloper in the domain of literature. Nausicaa was more probably a survival than an interloper, but most probably of all she was in the height of the fashion." (1897).

The poet and epigrammist, Nossis (c. 300 BCE)

Helen: A Production by Shannon Davis III:

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Helen of Troy

HELEN

by Ellen McLaughlin

A Production by Shannon Davis for University

Theatre

November 21 - December 7, 2014. The Hemsley Theatre, University of

Wisconsin--Madison. (Adults $23; Senior Citizens $21; Friends of UT, Students,

Children $16)

Dramatis Personæ

Helen..................................Anne Guadagnino

Athena................................Chelsea Anderson

Servant...............................Hillary Dido-Perrone

Io........................................Elena Livorni

Menelaus...........................Daniel Millhouse

Director.........................Shannon

Davis

Stage

Manager..............Angelique Phanthavong

Scenic

Designer............Andrea Alguire

Costume Designer........Amanda

Rabito

Lighting

Designer.........Rob Stepek

Vocal

Coach..................Michael Cobb

Dramaturgs....................Steffen

Silvis

Bridgett Vanderhoof

Technical

Director..........Vince Davey

Props Master...................Dana

Fralik

Sound

Designer..............G.W. Rodriguez

Assistant

Directors.........Cynthia Miller

Claire Mason

Dramaturg's Notes:

“All the argument is a cuckold and a

whore”—Thersites, Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida (II-iii-71).

Of the thirty-two extant plays of Aeschylus,

Sophocles, and Euripides, approximately half concern events surrounding the

Trojan War, whether before the conflict (Euripides’ Iphigenia in Aulis),

in the midst of it (Sophocles’ Ajax), or in the poisoned aftermath (the

three plays constituting Aeschylus’ Oresteia). Even the lone, surviving

satyr play, Euripides’ Cyclops, is a post-war incident from Homer’s Odyssey.

Euripides’ Helen is,

of course, named for the casus belli of the ten-year-long catastrophe;

the wife of King Menelaus, who abandoned husband and reputation for Paris,

Prince of Troy. Helen remains one of the greatest femme fatales of

ancient literature; a Jezebel, though one who never seriously pays for her

transgressions. Having created an excoriating portrait of Helen in his play The

Trojan Women, Euripides returned to her character, but approached her from

a novel direction, creating an odd, hybrid “tragedy,” which playwright Ellen

McLaughlin terms “one of the strangest plays ever written.”[i] “What,” Euripides asks, “if Helen wasn’t

actually at Troy?”

The lyric poet

Stesichorus, a century before Euripides, appears to have originated the idea

that Helen never arrived at Troy, but rather was whisked off safely to Egypt by

Hermes, while Hera confused both Trojans and Greeks by creating a phantom Helen,

over whom both sides battled. The story was elaborated upon by Herodotus in his

Histories, although the rational historian dismissed the phantom idea.

Richard Rutherford notes that Euripides alludes to this “alternative tradition”

near the end of his Electra, which, Rutherford suggests, was written

just prior to Helen,[ii]

revealing the innovative playwright’s interest in “counterfactual” readings.

The play also evinces Euripides’ new direction in his playwriting, one informed

by irony, if not occasionally farce, which can only be termed “tragicomedy.”

Structurally and

thematically, Helen appropriates Homer’s Odyssey, with its story

of a sea-wearied husband (“Seven circling years I spent on board ship”)[iii] and his reunion

with his faithful wife, complete with the requisite reversals (peripeteia)

and recognition scenes (anagnorises). If Euripides drafts Menelaus as

Odysseus’ double, his wayward, nymphomaniacal wife fatale has been,

according to Erich Segal, “Penelopized”:[iv] Helen is an innocent victim of

myth-mongering.

J.W Waterhouse, Penelope and the Suiters

The comic irony

informing Helen gestures toward the less scurrilous New Comedy of

Euripides’ dramatical descendant, Menander. But immediately following its

premiere, the play became fodder for comedy, as Aristophanes parodied Helen in

his play Thesmophoriazusae. Aristophanes, as was his wont, skewers

Euripides’ language and play structuring. Yet Euripides, in a surprising

metatheatrical moment in the play, signals that he is fully conscious of his

plot’s machinery. After Helen divulges her scheme for how she and Menelaus

might escape Egypt, complete with disguises, the very property of farce,

Menelaus replies, “your plan is hardly very original.”[v] In response to Thesmophoriazusae’s

spoof, Rutherford asks, “did Aristophanes feel that tragedy was beginning to

poach on comedy’s territory?”[vi]

Considering the trajectory of ancient Greek comedy, and the role Euripides

ultimately played, Aristophanes can be forgiven for his prescient anxiety.

McLaughlin’s adaptation

is a tragicomic pastiche with an Aristophanic conflation of narratives,

introducing the comically miserable Io into the action as an icon of

“exceptional female fate,”[vii]

becoming another reflection of Helen (both women are certainly plagued by

flies). And, as in any proper farce, Thersites’ “cuckold” and “whore” finally

meet in a bedroom, though McLaughlin’s conclusion is less comical than

Euripides’, erring more on a tragic note, as in Shakespeare’s own Trojan

tragicomedy, Troilus and Cressida.

Helen, for all

of its comedic handling of the “face that launched a thousand ships,” “implies

a bleak and pessimistic view of human action,” Rutherford writes. The Trojan

War “was fought for a phantom,”[viii]

suddenly revealing a horrifying level of futility. The whole Trojan enterprise,

to use the title of Barbara Tuchman’s superb study of war, was a “march of

folly” (Tuchman’s subtitle is “From Troy to Vietnam”). “Oh, it seemed like a

good idea at the time,” Athena tells McLaughlin’s Helen. “Something about

glory.”[ix] “Glory”

was a concept that had just taken a blow in Euripides’ Athens.

Helen is one of

the few plays for which we have an exact date: 412 BCE. Euripides was subtly

refracting a recent folly through an ancient one, as the perpetual

Peloponnesian War had just delivered a decisive Athenian defeat in 413 BCE. As

Helene P. Foley writes, “Helen was presented just after the disaster of

the Sicilian expedition, when an Odyssean reevaluation of military ambition may

have seemed particularly relevant.”[x]

The play now ably refracts our own martial history, both current and historic.

In her adaptation, McLaughlin’s descriptions of the Trojan War are to be read

as “the First World War, in all its lengthy absurdity and horror,”[xi] a horror for which

we are currently commemorating the centennial start.

Otto Dix, The Skat Players

Do we allow ourselves

to honestly analyze the doubles we see in the mirror? Mere illusion has

destroyed and bankrupted two civilizations in Helen, and the eponymous

heroine, innocent of any involvement in the madness, is herself forever trapped

in an troubling image; a myth. In Jean Giraudoux’s mordant play Trojan War

play, Tiger at the Gates (1935), the uncomfortable questions posed by

Euripides and McLaughlin arise:

Helen: If you break the

mirror, will what is reflected in it cease to exist?

Hector: That is the

whole question.[xii]

Steffen Silvis

[i] McLaughlin, Ellen.

“Introduction to Helen.” The Greek Plays. New York: Theatre

Communications Group, 2004. 121.

[ii] Rutherford, Richard.

“Preface to Helen.” Euripides: Heracles and Other Plays. London:

Penguin Books, 2002. 154.

[iii] Euripides. Helen.

John Davie, translator. Euripides: Heracles and Other Plays. London:

Penguin Books, 2002. 178.

[iv] Segal, Erich. The

Death of Comedy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001. 142.

[v] Euripides. Helen.

186.

[vi] Rutherford, Richard. 154.

[vii]McLaughlin, Ellen.

“Introduction to Helen.” 126.

[viii] Rutherford, Richard.

“General Introduction.” xxxi

[ix] McLaughlin, Ellen. Helen.

The Greek Plays. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 2004. 161.

[x] Helene P. Foley. Female

Acts in Greek Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001. 328.

[xi] McLaughlin, Ellen.

“Introduction” 127.

[xii] Giraudoux, Jean. Tiger

at the Gates. Christopher Fry, translator. New York: Oxford University

Press, 1955. 32.

The Mythological

Characters:

Athena:

She is the goddess of

knowledge, justice, wisdom, and learning. She also represents the strategic

side of war. She plays a large role as a mentor to Odysseus in The Odyssey,

as he travels home from Troy, a war tate Athena herself brought on after Paris

chose Aphrodite as the most beautiful goddess, and in return was promised the

most beautiful mortal woman by the Goddess of Love--Helen. Athena is a

character in many of the Ancient Greek plays centered on the Trojan War and its

aftermath: Aeschylus’ The Eumenides, Sophocles’ Ajax, Euripide’s Trojan

Women, Iphigenia in Tauris, Orestes, and the disputed Rhesus.

Helen:

Helen is the daughter of

Zeus and Leda, born from an egg alongside Clytemnestra, Castor, and Pollux.

Helen is conjured by both Christopher Marlowe and Goethe in their Faust plays,

as well as being a major character in other dramas: Kochanowski’s The

Dismissal of the Greek Envoys, Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida,

Giraudoux’s Tiger at the Gates, Mary Zimmerman’s The Odyssey, and

Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hofmannsthal’ opera, Die ägyptische Helena.

In Greek drama, she is the eponymous heroine of Euripides’ Helen, as

well as the villain in his Trojan Women. She is also in Euripides’ Orestes,

and Sophocles’ lost play, The Request of Helen.

Erté

Io:

Zeus lusted after the nymph

Io (a devotee of Hera's cult), and tried to hide her from his wife, Hera, by turning Io into a heifer.

Hera then demanded the heifer as a pet, and kept a close eye on her--indeed, Hera's servant, Argus Panoptes, who had one hundred eyes, was Io's watchman. After Zeus ordered Hermes to slay Argus, Io escaped

across the Ionian Sea to Egypt, though Hera cursed her with a stinging gadfly. In Egypt, ultimately, she marries one of the Pharaohs, and her descendants

eventually make it back to Greece as the Danaïdes, whose story forms Aeschylus’

play, The Suppliants. While the tie between Io and the Egyptian

cow-faced goddess Hathor (see image below) remains vague, they are both

obviously extensions of an ancient Mediterranean cult (the Canaanite town of Hazor, mentioned in the Tanakh, was a center for her worship). In her bovine state, Io

encounters Prometheus, who has been tied to the top of a mountain for giving

humankind fire, an encounter that appears in the Ancient Greek tragedy

(formerly assigned to Aeschylus), Prometheus Bound. While Io was also a

primary character in Sophocles’ Inachus, that play exists only in

fragments.

The d'Aulaires

Meneleus:

The mighty King of Sparta

and literature’s greatest cuckold. His injured pride sparked the long,

devastating Trojan War, which has assured him a prominent, if ambiguous, role

in the Western canon. He is one of the few Homeric characters to feature in both The

Iliad and The Odyssey, and he is a major character in Greek

tragedies, such as Sophocles’ Ajax. But he is a character that

Euripides’ continually returns to in his Andromache, Orestes, Iphigenia

at Aulis, The Trojan Women, and Helen.

Helen and Menelaus Meeting:

Menelaus’ wrath is such

that Helen’s life is in danger in Euripides’ The Trojan Women, though

she uses her famous wiles to win him back, while the native women of Troy,

including Queen Hecuba, suffer grievously. In Strauss and von Hofmannsthal’s Die

ägyptische Helena, Menelaus is still considering killing Helen long after

they have left Troy, while Homer has them completely reconciled by the time

Odysseus’ son, Telemachus, visits them in Sparta in The Odyssey. The

myth of the phantom Helen deployed at Troy, while the real Helen was whisked

off to Egypt (which forms the plot of Euripides’ Helen), appears to have

been developed by the lyric poet Stesichorus (circa 640-555 bce), which

Herodotus elaborated upon in his The Histories.

Paul Guiramand, The Second Abduction of Helen.